The UK government created a video game with a meter that tracks how extreme your thoughts are. Not your actions. Your thoughts. Pathways is a Home Office-funded video game deployed in British schools for children aged 11 to 18. Players control a white teenage character named Charlie through scenarios where choices affect an in-game extremism meter. Reach the wrong threshold and Charlie gets referred to Prevent, the UK's counter-terrorism program. Schools in Hull and East Yorkshire are using this right now. Children as young as 11 are being taught that their government tracks thoughtcrimes with the same infrastructure used to stop terrorism.

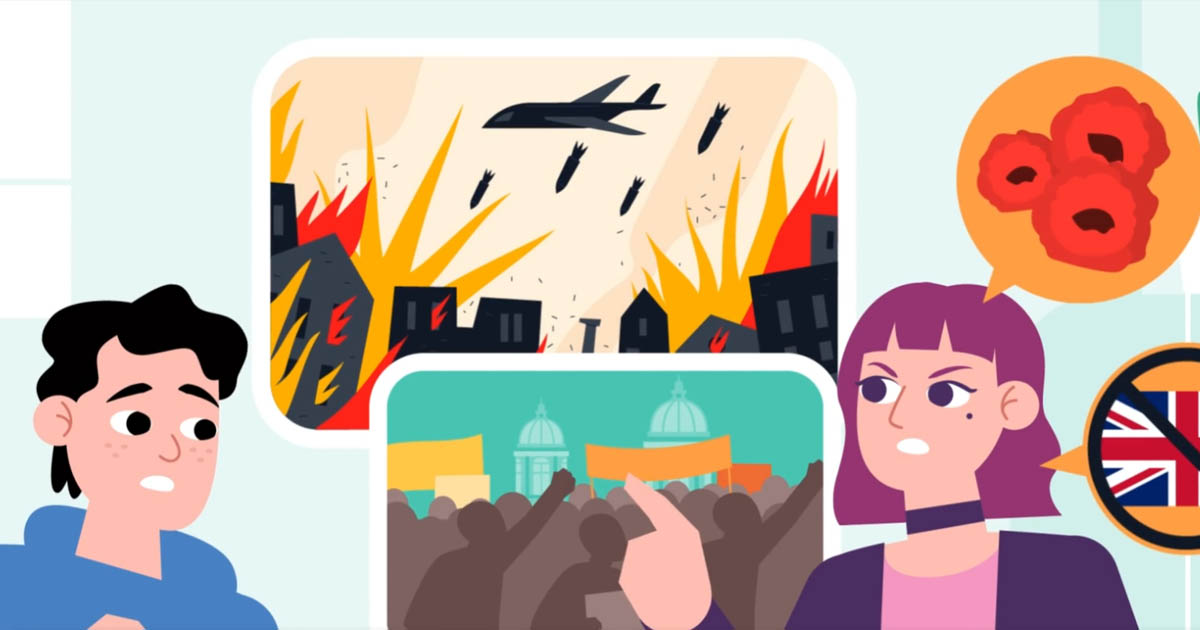

Early in the game, Charlie is outperformed academically by a black student. The player chooses whether to accept this or blame immigrants for stealing jobs. The latter increases your extremism score. Charlie encounters videos claiming Muslim men are stealing emergency accommodation from British veterans. Videos saying the government is betraying white British people. The game treats engaging with these claims as evidence of radicalization. Researching immigration statistics online is portrayed negatively. The game doesn't distinguish between reading propaganda and seeking facts. Both increase the meter. Both move Charlie closer to intervention. Some topics are off-limits. Some questions mark you as suspicious. The state decides which.

Multiple reports suggest most gameplay paths lead to a Prevent referral regardless of choices. The outcome is predetermined. The exercise is conditioning. Children learn that expressing unapproved political beliefs requires correction through counseling and workshops run by counter-terrorism authorities.

Prevent was supposed to stop terrorism. Axel Rudakubana was referred to Prevent three times before he walked into a dance class in Southport and killed three children in July 2024. Three referrals. Three chances. Three failures. His case was closed each time because he showed no distinct ideology. Prevent couldn't identify a triple murderer after three direct interactions. But it has resources to deploy thought-tracking games in schools. Resources to monitor teenagers who research immigration policy. Resources to build counseling programs for children who express wrong political beliefs.

The Southport attack triggered a 34% spike in Prevent referrals. Not because the program improved. Because the public became more vigilant. More reports flooded in. The system that missed Rudakubana three times now processes even more referrals, diluting its capacity further while teaching schoolchildren that curiosity is extremism. Prevent's defenders claim it has diverted nearly 6,000 people from violent ideologies. They don't mention how many of those 6,000 were actual threats versus teenagers who asked uncomfortable questions. They don't explain why a program that failed to stop a mass murderer should be trusted to determine which thoughts are dangerous in 11 year olds.

The game was developed by Shout Out UK with Home Office backing. Local councils in East Yorkshire created it amid rising tensions over migrant accommodation in hotels. Their solution wasn't to address the tensions. It was to teach children that noticing the tensions makes them extremists. Hull City Council called it teaching media literacy. Shout Out UK claimed it provides lifelong tools to safeguard students from harmful ideas. The Home Office praised Prevent's success. None addressed why questioning government immigration policy warrants counter-terrorism scrutiny. None explained why researching publicly available statistics is treated as a pathway to violence.

The game embedded the surveillance state into mandatory education and called it safeguarding. It taught children that some questions are dangerous. That some facts are suspicious. That political curiosity requires government approval. Then the internet got hold of it. The game featured a purple-haired goth character named Amelia who represents anti-immigration views. She was designed to repel teenagers. Instead, she became a viral meme within days. Reports claimed the game was disabled on January 14, 2026. It wasn't. The game is still live at shoutoutuk.org. The framework remains in British schools and anyone can play it right now.

Prevent isn't stopping terrorism. It's managing acceptable thought. A program that can't stop a mass murderer after three referrals has decided that teenage curiosity about immigration is a counter-terrorism priority. The game treats civic engagement as criminal suspicion. It tells children that expressing political beliefs without government approval is dangerous. That some topics require intervention. That your thoughts can be measured, tracked, and corrected.

British children are being taught that the state monitors their questions. That researching the wrong topics marks them for correction. That political beliefs require approval from authorities. That disagreeing with immigration policy puts you on the same spectrum as terrorism. The game's extremism meter isn't measuring danger. It's measuring compliance.

Prevent has a choice. Stop actual terrorists or police teenage thoughts. They chose thoughts. The bodies in Southport are the cost. Three dead children because Prevent was too busy building infrastructure to monitor schoolchildren's opinions about immigration. Three referrals that went nowhere because Rudakubana didn't fit the ideological profile the system was designed to catch. The UK government spent taxpayer money to teach 11 year olds that curiosity is extremism. That political questions are dangerous. That the state tracks your thoughts and corrects them through counter-terrorism programs. They built this system, deployed it in schools, and called it safeguarding. The game remains online. British children are still learning that questioning their government makes them terrorists.

Blackout VPN exists because privacy is a right. Your first name is too much information for us.

Keep learning

FAQ

What is Pathways and who uses it?

Pathways is a UK Home Office-funded video game deployed in schools in Hull and East Yorkshire for children aged 11-18. It tracks an in-game extremism meter based on the player's choices about immigration, politics, and British values. Wrong choices lead to Prevent terrorism referrals.

What gets you flagged in the game?

Researching immigration statistics, blaming immigrants for job competition, engaging with videos about migrant accommodation, and joining protests against erosion of British values all increase your extremism score. Reports suggest most gameplay paths lead to Prevent referrals regardless of choices.

Did Prevent stop the Southport attacker?

No. Axel Rudakubana was referred to Prevent three times before killing three children at a Southport dance class in July 2024. His case was closed each time because he showed no distinct ideology. Prevent missed him three times but deploys thought-tracking games in schools.

Is the game still being used?

The game was reportedly disabled on January 14, 2026 after a character named Amelia became a viral meme celebrating the views it was meant to suppress. The framework remains in British schools and Prevent continues operating with the same priorities.

Why does this matter?

The UK government embedded surveillance into mandatory education for children as young as 11. They're teaching kids that researching facts and asking political questions marks them for counter-terrorism intervention. Prevent failed to stop actual terrorism but built infrastructure to police teenage curiosity.